The PPL Radio Exam / Practice Test is something I knew very little about before going in for it. Before you can be issued your PPL licence, you must have completed all 9 written exams, the skills test and the radio exam. Googling didn’t really find much, and the instructors and everyone I asked didn’t give much away either, just saying “you’ll be fine”!

Here’s what happened…

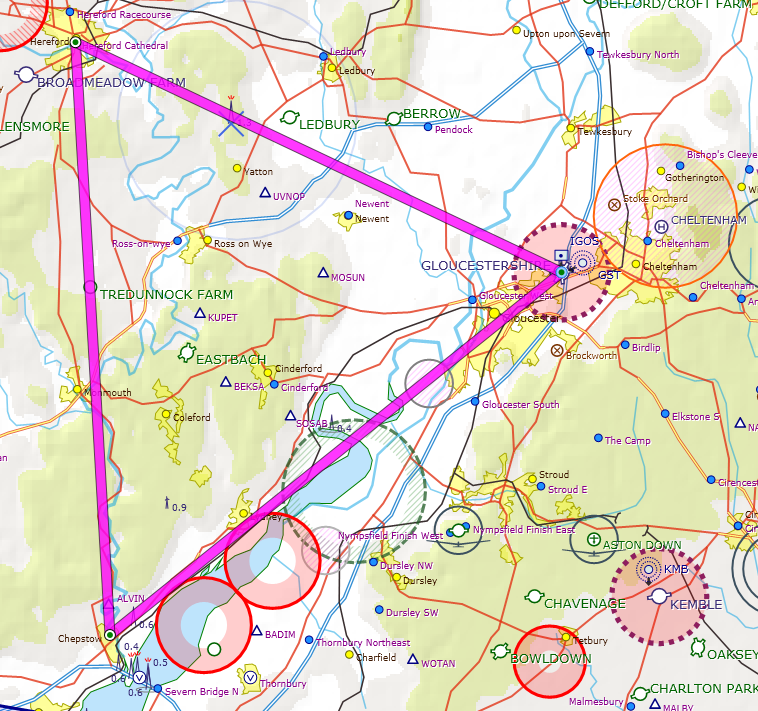

On arrival, I had a briefing with the examiner. He explained that we’d each have a laptop, with headphones and mic, and would be sat in different rooms. The laptop would show an aircraft flying along a predefined route. He gave me a couple of sheets of paper: a (made up) map showing a planned route, with airfields, danger areas, airways, CTRs, CTAs, and MATZs; a list of all the radio frequencies available that could be used along the route (airfields, LARS, MATZ penetration, FIR Information, etc); a PLOG for the ficticous route, complete with headings and estimated times; an instruction sheet, listing the sequence of events that would happen (eg, depart from airfield X, request MATZ penetration, obtain a traffic service, etc).

I then had half an hour to prepare on my own. I visualised the route and made notes of the things I’d want to do at key points along the route. As you’re allowed to make notes, I wrote a brain dump of the Urgency call order incase I became tongue-tied during the main event.

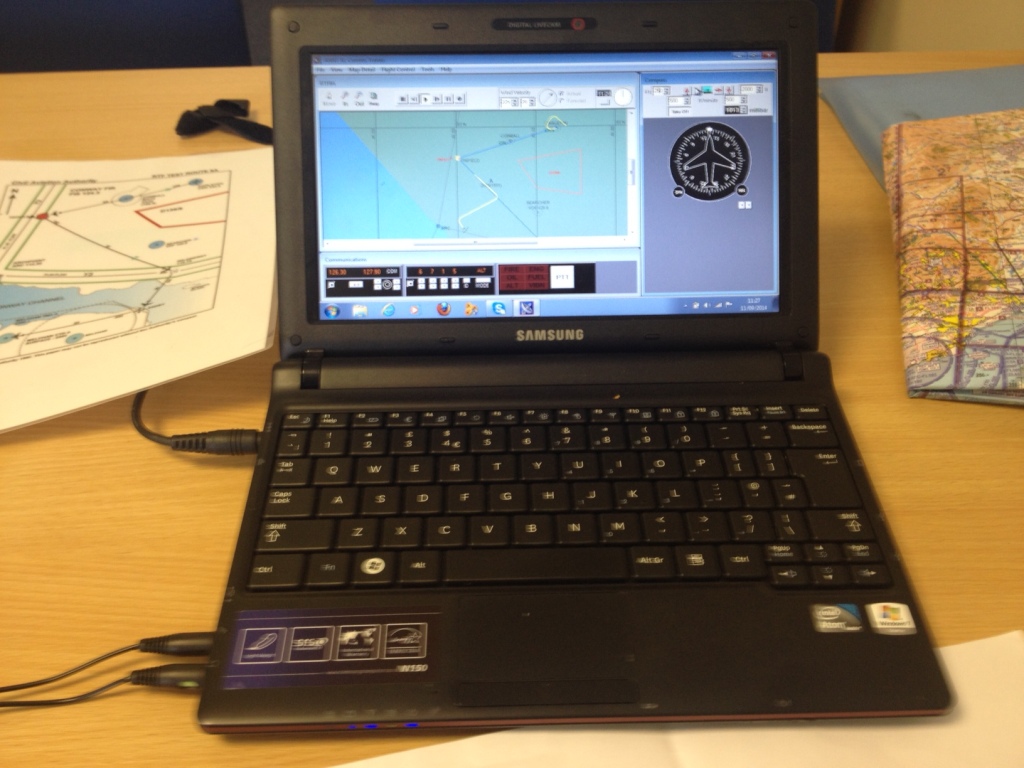

After the prep time, the examiner came back and asked if I had any questions. I didn’t, so he brought the laptop in to the room and gave me a quick demo of how it all works. On the screen is a moving map, with an aircraft. There are controls for heading and buttons to turn left and turn right. At each turning point of the route, I’d need to select the correct heading and click the turn button. This is the only control input for the flying that was necessary. He was keen to emphasise it’s not a flying test, nor is it a test of being able to accurately turn at the right places – it’s all about the radio, with the map being used as a visual aid to think about what calls are needed, and when.

In addition to the moving map and aircraft controls, icons for transponder and radio are at the bottom of the screen. You click the knobs and the frequency/ident changes. Just like the real thing. The red/orange lights represent possible problems such as engine failure, oil pressure etc. If these light during the test then I am to report a Mayday or Pan Pan urgency situation.

I then had 10 minutes to play around with the controls and get used to it, before we started the real test. Everything seemed to work correctly and was easy enough to use, so I said I was happy to start. The examiner left the room and went next door. We did a quick test to make sure we could hear each other ok (through the headphones) and then the exam started.

- I started on the ground in an ATC airfield. I had been given the ATIS information. I requested radio check, then called for taxy. I then called ready for departure, but had to hold position for a landing aircraft. I was then given a “line up and wait behind” clearance, followed by a clearance to take-off.

- The airfield had a combined tower/approach, so no frequency change was necessary. I was given a basic service. This part of the route goes directly through a MATZ, so I had to call the MATZ Penetration service to request MATZ penetration and traffic service. I was given clearance through it, given a squawk and told to report on leaving the zone.

- Upon leaving, I had various traffic reports given to me, which I had to acknowledge.

- After turning at the first waypoint, I again had some more traffic reports. You have to be careful to listen out, as some messages are for you but some aren’t. There are lots of pre-recorded audio clips of other pilots, and the examiner (the radio controller) responds to them too, so just because you hear his voice doesn’t mean he’s talking to you!

- I heard a MAYDAY call that wasn’t answered, so it was up to me to relay it. I relayed it, it was acknowledged, and then shortly later the originating aircraft cancelled their mayday, which again I had to relay. Emergency over.

- The LARS service told me they were closing for the day, and to reset my squawk.

- After resetting to 7000, I called the FIR Information service for a basic service.

- The script at this point said that I must request a true bearing from a VDF service along the route, so I requested frequency change to them, obtained a True Bearing, then changed back to the FIR Service for a basic service.

- At the end of this leg, I was approaching a Class A CTA, which meant I needed to obtain a Special VFR zone transit. I requested frequency change, and passed my message, asking for a Special VFR Zone transit. Again, another squawk and shortly afterwards they had identified me and cleared me to transit their zone.

- Whilst in the zone, flying towards the destination airfield, I received a radio call informing me that my destination airfield had closed and would likely be closed for several hours. I acknowledged and requested to divert to their airfield, which was acknowledged. They handed me over to tower, who told me to join left base.

- I made the various calls during landing, and was given clearance to land.

Shortly after, the test was over and the examiner came in to tell me I had passed 🙂

He was pleased with my performance. The only thing he took issue with was me getting a basic service from the FIR for only a couple of miles, before then switching for VDF, only to switch back again. Whilst not technically wrong, in real life the FIR service is so busy that it can be difficult to get your message in, so probably wouldn’t have been able to get the initial basic service.

Exam passed, paperwork signed, now all I need to do is the final skills test…