After many weeks of cancellations due to the terrible weather, I finally got back up in the air recently for my first navigation lesson. A couple of weeks before hand, because of the bad weather we decided to spend a couple of hours doing ground school in preparation for the upcoming navigation lessons. The majority of the remaining lessons focus on navigation and as you’d expect, it’s not something you’d want to be crap at.

There are so many elements of flight planning to consider before the flight. At first it can seem quite daunting. Here are just some of the things to consider:

- Weather – at departure airfield, destination airfield and en-route

- NOTAMs (Notice To AirMen) – temporary notices and restrictions, you must check for any notams along your planned route

- Royal Flights – you need to phone the royal flight information line to ensure your planned route doesn’t pass near any planned royal flight (royal flights create temporary restricted airspace you have to avoid – otherwise face an interception by an F/16)

- Fuel – how much fuel is required for your journey, including a contingency amount

- Weight and balance – are you able to fly the planned route with the fuel, passengers and luggage that you are planning to take?

- Alternatives – what airfields can you divert to if the weather turns bad?

As well as all this, you have the job of planning which route you want to take. This sounds like a fairly straightforward process – and can be – but can get very complicated very quickly if your route is surrounded by complex restricted airspace.

In principle, to plan your route, take your aeronautical VFR chart (map) and draw a straight line from your departure airfield to your destination. This will be the shortest route. Next, look along the route to see if it passes through any controlled airspace, danger areas, restricted areas, gliding sites, parachute drop zones and other potential hazards. You then need to alter your route to accommodate all these things.

Then you need to measure the distance of each part of your route, as well as the angle between each point. Once you have the distance (in nautical miles) and the true heading, you plot them in a PLOG (which is essentially your route, written down on paper). You then need to calculate the heading to fly, and the estimated time taken to each fly each leg. Both these things very much depend on the wind. To do this, you use a flight computer. A flight computer sounds very fancy and technical, but in reality is 1950’s technology – a simple slide rule.

The flight calculator uses the triangle of velocities to give you a ground speed and wind correction angle, given the wind speed and direction and your intended heading and air speed. You plot the heading on your PLOG, then flip the flight calculator over to calculate how long it will take to fly the distance at that speed. Write the estimated time in the PLOG. Finally, you need to convert from true heading to magnetic heading and compass heading. Magnetic heading is true direction adjusted for variation (you learn more about this when studying for the nav exam), whilst compass heading is magnetic heading adjusted for the deviation of your aircraft’s compass. Got all that? Simple.

So now we have a route, with headings to fly, distances and times for each leg. What about altitude? How do you decide how high to fly? Firstly, you go back to your chart and look along each leg of your route. You need to look 5nm either side of the planned track for the highest feature – terrain or obstruction – shown on the map. For example, you may see a wind turbine with an indicated altitude of 1,235ft above sea level. Or it may be a hill that peaks at 1,354ft. Now we calculate the minimum safe altitude. Round the highest point up to the next 100ft, eg (1235 to 1300). If it’s terrain, you need to allow for a potential obstacle on the top of it (as VFR charts don’t show obstructions below 300ft). So take the rounded height and add 300ft. Finally, add 1000ft to give us our MSA.

Because the UK VFR 1:500,000 chart doesn’t depict terrain below 500ft and obstructions below 300ft, even on what appears to be a clear patch of land you have an MSA of 1,800 ft. This is because you could potentially have an obstruction of 299ft on terrain of 499ft. When rounded up, this gives us 800ft, plus the 1000ft = 1800ft.

We don’t have to fly at or above the MSA, we can safely fly below the MSA in good visibility with clear sight of the surface and of 10km or more ahead. So, why do we calculate it? It’s a safety net, there for us if we inadvertently fly in to instrument meteorological conditions (IMC) for which our licence doesn’t allow us to legally fly. This would be a bad place to get to, but it can happen. If it does, the first thing you should do is ensure that you are flying at or above your MSA. So even if you cannot see the ground or terrain, you know that you are above the highest terrain around you and therefore are not at risk of controlled flight in to terrain.

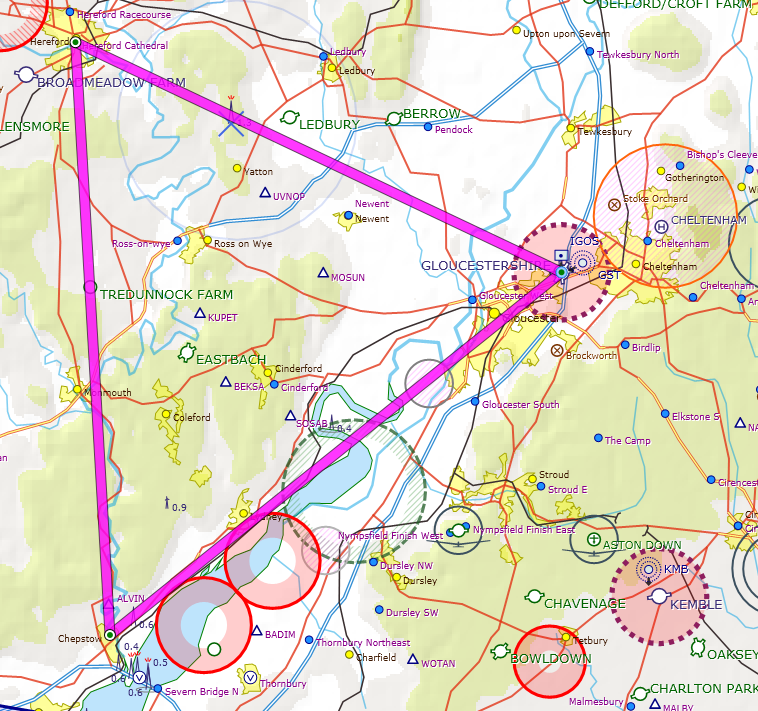

After learning all this, I planned my first route. We’d be flying in a triangle, from Gloucester down to Chepstow, up to Hereford and back down to Gloucester. Each leg is about the same distance, but with today’s wind they would take 18 minutes, 13 minutes and 11 minutes respectively.

The principles of navigation rely on dead-reckoning, not GPS. It’s all about timing. Before setting off, you mark the quarter, half and three-quarter way points of each leg on your map. Then when in the plane, you start a stopwatch at the beginning of each leg. Because you have calculated an estimated time for each leg, when you have been flying for quarter of the estimated time, you look on the chart to see what you’d expect to see on the ground. Then you look on the ground and determine whether you are where you expected to be.

You could be somewhere different to where you were expecting to be for numerous reasons – the wind could be stronger, lighter or in a different direction to forecast. You may have accidentally been flying the wrong heading. There are a bunch of things you can do to make corrections but I’ll cover this in another post.

When you arrive at each waypoint in your PLOG, you’re expected to do the four T’s (in order):

- Turn – to your next heading

- Time – note the time of the turn, reset your stopwatch, update your PLOG to reflect actual and revised estimates

- Talk – give a position report on the radio (“Gloucester Approach, G-GFCA, Position Report, turned Chepstow time 44, 2500ft on 1019, Estimate Hereford time 55”)

- Task – carry out any other tasks such as changing pressure settings, FREDA checks etc

So after all that theory, time to fly. After checking the airplane (yet another element of pre-flight planning!) we were soon taxying out to the runway…

After being cleared for take-off, as I entered the runway I had another task to add to my ATPL runway checks (Anti-Collision Light, Transponder, Pitot Heat, Landing Light) – start the stop watch! Soon we were climbing away.

My instructor introduced me to some more checks:

At 300ft – FEL checks:

- Flaps retracted

- Engine temperatures and pressures

- Landing light can go off

Then at 1000ft, RAF checks:

- Radio

- Altimeter

- Fuel pump off

At around 1000ft it’s time to turn to your first heading. After turning on the heading, perform a gross error check to make sure you’re flying in roughly the right direction. Look at the map and the ground to make sure you’re heading the right way.

Everything happened so quickly. Before I knew it, we were at the quarter-way time. I looked at the chart and I looked down below, and we were in the right place at the right time. Same with the half way point. Three-quarter way point was on time too. Finally we reached Chepstow with the Severn Bridges off to our left. I turned to the new heading, noted the time and filled out the ‘estimate’ time for Hereford. I then got on the radio to give my position report.

So far so good, and on it continued until Hereford. We arrived there on schedule and turned back towards Gloucester. However on this leg, we appeared to be to the right of our intended track, so I had to correct for this by turning left. Back on the ground after some reflection, I concluded that I turned too early. I could see Hereford but we were not flying above it. Looking at my GPS log, I actually turned about 2nm too early, so even though we were flying the correct heading, we ended up 2nm south of where we wanted to be. Not a biggie – and useful learning for the future. Make sure you’re overhead the place – being able to see it is not the point to turn!

I then made a standard overhead join and joined a fairly busy circuit. Landing went well.

Here’s a 30x faster video of the entire flight:

Next lesson we’ll be doing the same route, but in reverse.